Takeaways:

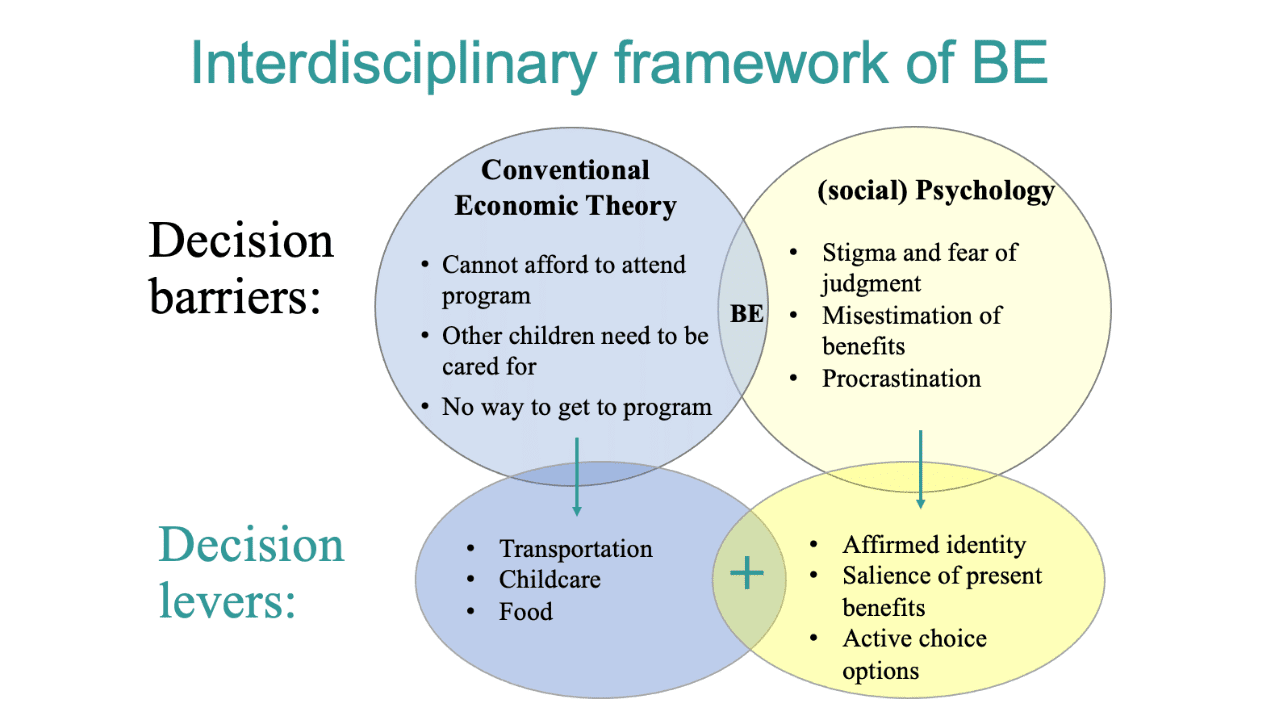

- BE combines economics with social psychology and cognitive decision making.

- Decision making in the realm of family life and parenting is composed of multiple micro-decisions.

- BE offers insights on why some families do not engage in evidence-proven programs by recognizing caregivers as active decision-makers with complex contexts.

- With slight design adjustments during micro-decision junctures, child and family policy programs might be able to boost family participation and engagement.

What is Behavioral Economics

A mother, let us call her Madison, intends to breastfeed her child exclusively for the first six months after consideration of the information she has read about the benefits to her and her child. After a few months, however, she adds formula even though breastfeeding has been going well and there have been no other significant changes to her circumstances. Why did Madison deviate from her intentions? Adding formula likely reflected a decision that goes much beyond cost-benefit analysis as conventional economic theory might claim: Madison’s social environment, beliefs, and 'in the moment' experiences also likely played a role in her decision (1).

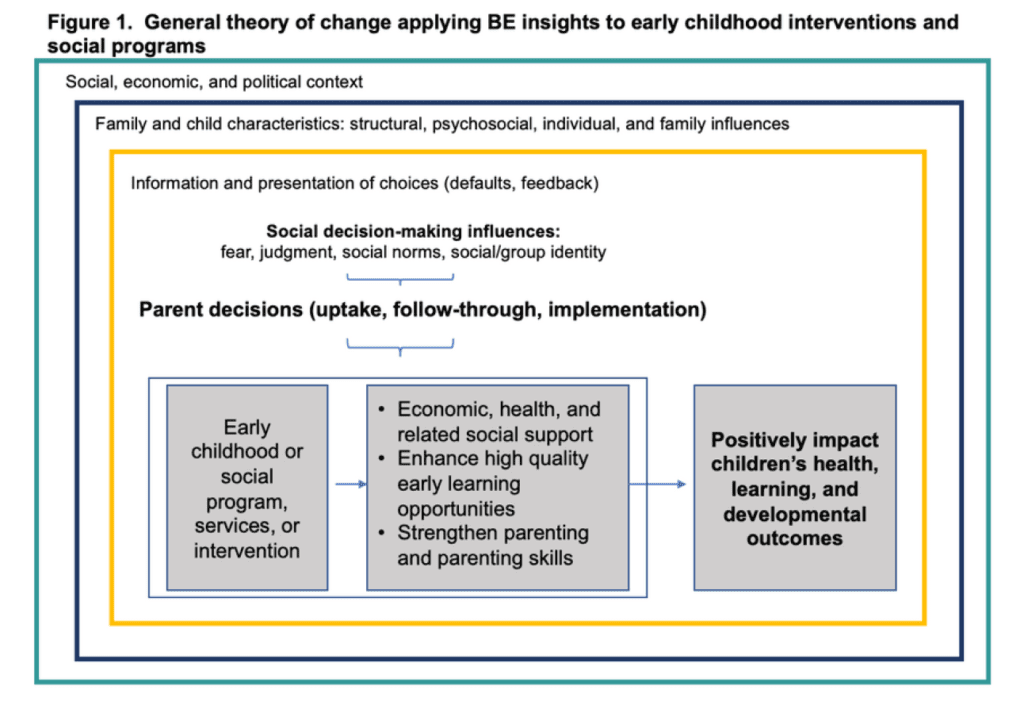

Behavioral economics (BE) combines economics with social psychology and cognitive decision-making to offer a broader framework for understanding factors that affect people’s decisions and actions (2,3). BE provides a way to examine how decisions can be shaped not only by information and costs but by how choices are designed, as well as the context and circumstances of the moment in which decisions are made (Figure 1). Choice design, or architecture, includes the format, timing, presentation, presumed defaults, and source of delivery. BE offers away to recognize that the context and circumstances around decision-making are both economic, such as time and money, and psychological and social, depending on availability of cognitive resources like attention and social environments. These factors influence human behavior and can interrupt or facilitate certain desired choices and outcomes (4).

A BE View of Decision-Making

Decisions in the realm of family life and parenting are not a series of one-time, large decisions but rather a sequence of multiple micro-decisions (4). By breaking down the decision-making process, BE helps to identify junctures or crucial points in which micro-decisions are made and can create paths that inform larger decisions.

Several micro-decisions contribute to caregiver engagement with child and family programs:

- Sparking initial interest

- Signing up

- Attending

- Applying the information learned on a daily basis

Before each step is a decision juncture to follow the desired decision-making path: developing interest, interest into intention, intention into follow-through, and follow-through into external practice (4). Small choices, or micro-decisions, such as picking up pamphlet, can facilitate or interrupt these decisions (1). Micro-decisions do not occur in a vacuum, but in the daily contexts of a caregivers’ life.

Factors that Influence Decision Making

Economics is a constructive discipline, but also idealizes people who make economic decisions as calculating and rational. However, psychology offers the important view that decision-making can be messy and that the human brain and people’s available cognitive or mental resources factor in (2). Human beings do not conduct a complete cost and benefit analysis for each decision, nor even have stable preferences over time; we have mental resources that can be easily taxed (i.e., experiencing cognitive load), are subject to be influenced by contexts and are persuaded by psychological biases (1,5). These include:

- Humans have limited attention and processing ability. If a person is overwhelmed with decisions, concerns, and/or emotions, they may make a decision that does not match their intentions.

- Humans often prioritize the present over long-term benefits. As such, a person may make decisions that may be rational in the short term but are not in their best interest in the long run (2,4).

- Humans are subject to social pressure and social norms, whether explicit or implicit, spoken or unspoken. For example, individuals may listen to a trusted authority figure in their life more than an expert or someone impacted by a particular situation.

- Humans look for information that already agrees with what they believe and dismiss information that contradicts or challenges their beliefs, leading to misinformed decisions. This is called confirmation bias.

- Humans can experience identity threats such as racism and classism which can lead to psychological responses such as stress, anxiety, and avoidance behaviors. These can lead to decreased self-image and negatively affect the decision-making process (4).

These decision-making factors can contribute to choices that might not be intended or desired, or to choices that other social agents (e.g., the government, a director, a supervisor) had not anticipated. Behavioral economics offers a way to understand these various factors that affect the decision-making process and ways to ease it through, for example, alleviating cognitive demands and the disruption of some of these social-psychological factors.

Applications of Behavioral Economics in Child and Family Policy

Child and family policy share the goal of positively supporting children’s development. The well-being of children depends upon the environment and circumstances of caregivers, yet few policies center their design on the actual (vs. incentivized or intended) decision-making of caregivers in the context and circumstances of their daily lives. Behavioral economics can help guide how public investments can support caregivers’ intentions.

In the realm of child and family policy, program leaders and policymakers alike worry about participation in programs - especially when programs aim to have large or universal population reach or scale (4). Policymakers at the national, state, and local levels invest in programs and services designed to improve family well-being and support children's healthy development (e.g., early learning, nutrition, parenting, and afterschool programs). The level of participation varies widely across these programs from near universal (e.g., K-12 schooling) to much lower (e.g., parent education programs and nutrition services). BE offers insights on why some families do not fully engage in programs designed to improve well-being and support healthy development by recognizing parents as active decision-makers with complex contexts (4). Through understanding these contexts and human biases, a BE framework can reorganize the decision-making process in programs to better support follow through of the intentions of caregivers.

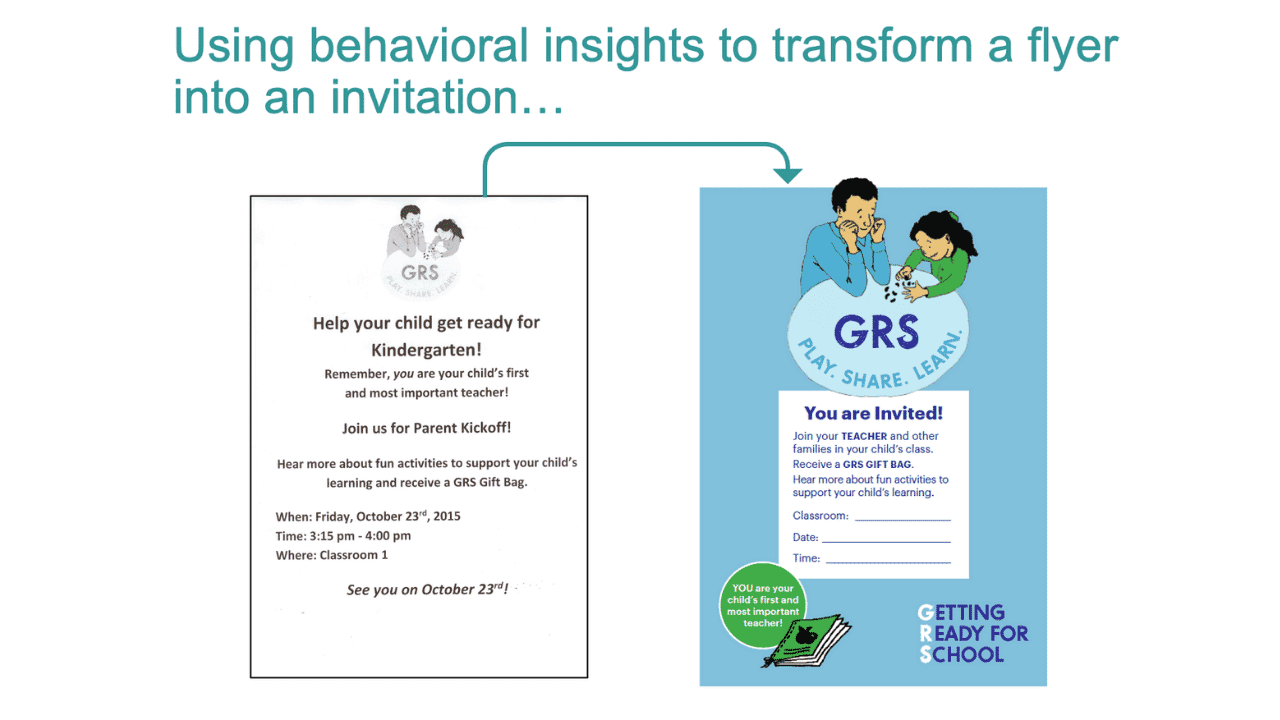

With slight tweaks, or “light touches,” and design enhancements at carefully chosen micro-decision junctures, child and family policy programs might be able to boost family participation and engagement in low-cost ways and at population scale. For example:

1. Changing the Choices

- Including fewer choices. Despite common thought, more choices at a time can overwhelm a decision-maker and lead to indecision. Instead, include fewer decisions at a time. If needed, space out the number of decisions (3).

- Change opt-in to opt-out. Instead of requiring decision-makers to act to join the program, set the default to enrollment in the program, requiring individuals to opt-out if they do not wish to participate (3,6).

- Change phrasing of options. If an opt-out choice is inappropriate or not feasible for a decision, present decisions in terms of active gains and losses so that parents can quickly understand the decision. For example: in documents to sign up for a class, instead of “Yes” and “No” options, use “Yes, I will attend this class and I understand that I will receive quality instruction” and “No, I will not attend and I do not wish to receive quality instruction" (5).

2. Social Belonging

- Group-based work. With the inclusion of caregivers and families in planned activities and/or sessions, programs can build positive peer influences and community among all participating families, creating a sense of social belonging.

- Setting new norms. Establishing norms is difficult but by introducing programs at new contexts or situations, programs can build social norms for those contexts. For example, introducing educational programs to caregivers soon after children start school creates the norm of educational programs for their children.

- Social network. Through caregiver testimonials, video endorsements, and letters from authority figures, programs can build the social support in the community (4).

3. And More!

- Self-affirmations. To combat identity threat, programs can use pride-based self-affirmations to increase caregivers’ self-image and fight against fear of judgment. Examples include supportive postcards or texts that remind caregivers of their successes (7,8).

- Reminders. In the hectic days of caregivers, program events, decisions, and “to-do’s” can easily and understandably be forgotten. Reminders, though, can take some of the effort off of caregivers and onto the program. Reminders should be close to the date of the event or action, personalized for the caregivers, and short and easy to read (think a tweet!). Text reminders are currently common in program participation studies (9,10).

- Small Incentives. To encourage and alleviate some stresses around participation, programs can offer small incentives for programs and events – such as babysitting, food, or a small gift (9).

These enhancements or “light-touches” can ease the burden of decisions off of caregivers while still preserving their agency and free-will to participate (or not) in a child and family policy program. Programs, in this way, smooth the path for caregivers and their children to participate in programs and services with affordable design enhancements or “program design boosters.” However, behavioral economics and these nudges must be used with care. All decisions must preserve freedom of choice, not be coercive or manipulative, and be easily reversible (5).

References

- Hill, Z., Spiegel, M., Gennetian, L., Hamer, K.-A., Brotman, L., & Dawson-McClure, S. (2021).Behavioral Economics and Parent Participation in an Evidence-Based Parenting Program at Scale. Prevention Science.

- Mullainathan, S., & Thaler, R. H. (2000). Behavioral Economics. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economics Research.

- Thaler, R. H., & Sunstein, C. R. (2021). Nudge: The Final Edition. New York: Penguin Group.

- Gennetian, L. A. (2021). How a Behavioral Economic Framework Can Support Scaling of Early Childhood Interventions. In J. A. List, D. Suskind, & L. H. Supplee, The Scale-Up Effect in Childhood and Public Policy. New York: Routledge.

- Hill, Z., & Spiegel, M. (2017). Harnessing Behavioral Economic Insights to Optimize Early Childhood Interventions. CFP Consortium Webinar. Society for Research in Child Development.

- Gennetian, L. A. (2017). Behavioral Insights to Support Early Childhood Investments. Retrieved from beELL: http://beell.org/img/item-1-LGennetian_BSPA_2017_conference_remarks.pdf

- Spiegel, M., Hill, Z., Gennetian, L. A., & Friedman Levy, C. (2017). Self-Affirmation and Parenting Programs. Retrieved from beELL: http://beell.org/img/APS_2017.pdf

- Hill, Z., Spiegel, M., & Gennetian, L. A. (2020). Pride-Based Self-Affirmations and Parenting Programs. Frontiers in Psychology, 910.

- Friedman Levy, C., & Gennetian, L. A. (2017). Using Easy, Attractive, Social, and Timely Principles to Engage Parents in Early Childhood Interventions. Retrieved from beELL:http://beell.org/img/EAST_memo_Oct21_2017.pdf

- Gennetian, L. A., Marti, M., Kennedy, J., Kim, J., & Dutch, H. (2019). Supporting parent engagement in a school readiness program: Experimental evidence applying insights from behavioral economics. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 1-10.

Behavioral Economics: Q&A with Dr. Lisa Gennetian

Q1: Why is the implementation of behavioral economic strategies so important in child and family policy?

It is important to bring a behavioral economics perspective into Child and Family Policy for two reasons. One, we often do not see child and family programs having the impacts that we think they should have, based on theory or implementation, because of sticking points that act as barriers to participation and engagement. For example, we could build this amazing program with a lot of structural support, but parents may not attend because they do not know anyone in the program or don't trust the program's intentions. Two, if we started with a framework that included both the ingredients for children's development and the science of parent decision making, we would design from the get-go very differently.

"I engage in this work to try to bring a proactive way to incorporate parent decision-making as a critical piece of the design of programs, services, and policies for children and families."

Dr. Gennetian

There is a lot of promise for both uses of behavioral economics. I engage in this work to try to bring a proactive way to incorporate parent decision-making as a critical piece of the design of programs, services, and policies for children and families to increase their reach and impact.

Q2: Why use a behavioral economic framework to understand scaling issues in child and family policy programs?

Early childhood innovations usually come from the expertise of child development scholars. Their lens focuses on supporting children, whether that is preventing something bad from happening or making sure they are surrounded by all the ingredients for healthy development. So, what is missing from that lens? The childhood development perspective does not always bring the broad-based tools and experience to think about the whole family and how people are engaging with programs and contexts. Without those tools and experience, it is hard to move programs from really promising ideas to large-scale projects.

"I like to think of behavioral economics as bringing the best of psychology and economics together, to become the discipline that can help move any kind of public policy or intervention into scale."

Economics brings a good decision-making framework for scaling, but also some strong assumptions about how our brains work and how we interact in the context of society. Psychology informs economics that humans are not computational machines, and that context does matter. Together, these two disciplines form behavioral economics.

I like to think of behavioral economics as bringing the best of psychology and economics together, to become the discipline that can help move any kind of public policy or intervention into scale. I cannot imagine how you scale without understanding the context in which people are supposed to engage with the programs as well as how to set up systems so that they can make decisions efficiently and follow through.

Q3: Are the “light-touches” of behavioral economics—such as changing decisions from opt-in to opt-out—paternalistic? Why or why not?

When you are in the business of policymaking or program design, you think about structuring choices and how that intersects with agency, freedom, and free will. One error that I believe many U.S. policymakers and program leaders fall into is the idea that ‘opt-in decisions preserve free will and all intentions.’ We know that is a mistake. We know that we fall into inertia, and we do the easy things when there are hard things in front of us. So, to me it is well intended but wrong-headed policymaking to assume that voluntary enrollment always protects people and their intentions.

"I think we need to get into the mindset that the way we design choices intersects with the way we make choices. This helps free us from this idea that structuring choices always interferes with people's agency

and free will."

The second, related point is that there is always a default. What happens if you do nothing? Someone is making that decision for you: the government, a teacher, superintendent of schools, the director of a program. If you do not sign up for 401k benefits, it means you will not receive those benefits. Someone made the decision to design it that way, and therefore, you default into not getting them. One thing that is needed in policy making is a mindset that the way choices is designed intersects with the way people make choices. This helps free us from this idea that structuring choices always interferes with people's agency and free will.

The paternalistic part of this is recognizing that someone is designing choices, but the reality is we are living it anyway. I want you to think about your everyday decisions and actions, the things that you do automatically. Someone already designed those choices for you.

There is a lot of responsibility around how we redesign choices. We have to be careful about what the default is and how that intersects with people's well-being. We have to be mindful about choice structures and its implications. For example, an employer in the UK initiated an opt-out savings retirement plan that implied that the employee accepted the way the funds were being invested. In this case, though, the investment of funds was quite profitable for the person in charge of creating the funds. This is an example of manipulating for profit-making purposes, not restructuring choices for the social good. That is the distinction I try to make.

Q4: How does the behavioral economics framework address the impact of racism and classism that so many families experience—maybe even in other child policy initiatives?

This is part of my own revamping, reeducating, and re-pivoting myself as a poverty scholar to to integrate the experience of race, racism, and histories of exclusion and oppression as front and center.

"One of the most powerful ways behavioral economics has changed how I come at policy design and evaluation, is it switches the perspective to not what I think you need, but let me see where you are at, and how your experiences are with systems, raising families, juggling work."

One of the most powerful ways behavioral economics has changed how I have come to think about policy design and evaluation is that it switches the perspective to not what I think someone needs or what the best scientists think someone needs, but rather to understanding their current circumstances and situations and acknowledging how their circumstances have been shaped by past experiences with systems, their own histories, and the challenges of juggling and balancing family life with everything else. This is a human and lived experience first approach.

The BE framework opened the door to understanding how everything from biases, to preferences, to values, to experiences that might reflect history or current circumstances, can be translated into better design through a behavioral economics lens. BE is not a panacea for poverty or racism or structural inequality. However, I believe that behavioral economics helps with our thinking of improved design and programs and services that can do better in incorporating experiences of racism, but it is not the discipline that alone can dismantle racism.

About the Authors:

Grace O'Connor is a senior at Duke University seeking a Program II degree in Child Rights, Policy and Development. Grace worked as a research assistant for the Center for Child and Family Policy during summer 2021.

Lisa A. Gennetian is the Pritzker Professor of Early Learning Policy Studies in the Sanford School of Public Policy, and a faculty affiliate in the Center for Child and Family Policy at Duke University. Her expertise includes behavioral economics and social policy.